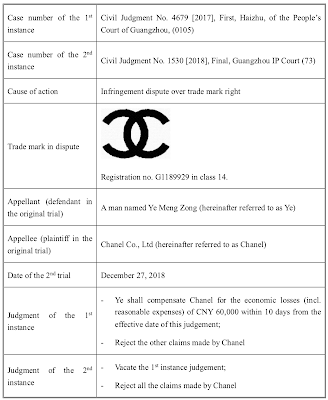

Recently, Chanel Co., Ltd. lost a trade mark infringement case regarding its ‘Double C’ logo in China. The full text of the decision can be visited via here (Google translatable).

The case has has drawn wide attention and, mostly, negative comments.

Does this seemingly-counterintuitive loss indeed, well, err? This Kat is putting her paws on the inquiry…

On 7 June 2016, together with the representatives of Chanel, Guangzhou Haizhu District Administration for Industry and Commerce (Haizhu AIC) carried out a detailed investigation into a local jewellery store operated by Ye. The representatives on the spot identified several products carrying the pattern, or with the shape of, the ‘Double C’ logo, which seemingly infringed Chanel’s exclusive rights to use the registered trade mark. Later on the same day, Haizhu AIC decided to file the case and conduct further investigations; then on 30 September, by issuing the No. 315 [2016] Administrative Punishment Decision, the agency confiscated the goods in question and required Ye to pay a penalty of CNY 80,000, based on the ‘established’ trade mark infringements.

Ye paid the fine and did not file any appeal for reconsideration.

The 1st instance

Chanel then filed a lawsuit with the Guangzhou Haizhu District People’s Court (Haizhu Court), seeking an order for Ye, the alleged trade mark infringer, to pay compensation totalling CNY 100,000. Despite the seeming unfairness that lies in the disparity in strength/size/resources between the two parties, Chanel’s protective approach is not surprising, and it is very much consistent with Chanel’s active brand-protection agenda (e.g. ‘no Shanel’, ‘no number 5’).

Ye responded with two main arguments: (1) his store was merely a franchise store of Zhoubaifu, a brand that belongs to Hong Kong ZhouBaifu Jewelry International Group Co., Ltd (Zhoubaifu Ltd), meaning only the products that had passed the quality inspections conducted by Zhoubaifu Ltd were allowed to be sold in Ye’s store, and those products all contained the registered trade mark of ‘Zhoubaifu’ – far from being similar to any of Chanel’s trade marks; (2) Ye actually had done little damage to Chanel, considering that there were only a total of 8 products with the sum of CNY 6,000 tag price involved, and they were not being sold.

The Haizhu Court sided with Chanel’s claims and ordered Ye to pay compensation of CNY 60,000 within 10 days from the effective date of the judgement, which was determined in view of ‘the level of harm, nature of business, business scope, scale of operation, time of infringement, infringement area, value of infringing goods’, among other factors.

The 2nd instance

After the 1st instance judgment, Ye appealed to the Guangzhou Intellectual Property Court (Guangzhou IP Court) with two claims: (1) the ‘infringing goods’ were identified by the on-site evaluation conducted by Chanel’s representatives, which lacked procedural credibility; (2) Ye’s silence regarding the No. 315 [2016] Administrative Punishment Decision did not exclude the possibility of enforcement errors being made by the administrative agencies.

After the hearing, the Guangzhou IP Court defined the primary issue as whether Chanel’s exclusive trade mark rights had been infringed by Ye, which, in essence, ‘involved the question of whether the shape of the (allegedly infringing) products, alone, could be deemed as infringing’. The current legal framework in China does not provide any direct or specific answer to this question.

A possible relevant provision is Article 76 of the Regulation for the Implementation of the Trade Mark Law of China:

The use of a sign which is identical or similar to another person’s registered trade mark on the same or similar goods as the name or decoration of the goods, thus misleading the public, constitutes an infringement upon the exclusive right to use a registered trade mark prescribed in subparagraph (2) of Article 57 of the Trade Mark Law.

So, whether ‘the shape (of product)’ falls into the scope of ‘decoration’? The Guangzhou IP Court opined that they are two different concepts without intrinsic relevance.

The analyses then went back to the basics to establish trade mark infringement:

1. Used as trade marks?

Under Chinese law, ‘the use of trade mark(s)’ is the prerequisite of infringement. And ‘use of trade mark’, according to Article 48 of the Chinese Trade Mark Law, refers to:

…the use of trade marks on goods, the packaging or containers of goods and the transaction documents of goods, as well as the use of trade marks for advertising, exhibition and other commercial activities for the purpose of identifying the sources of goods.

In this case, the products in question were sold with labels of ‘Zhoubaifu’, under the roof of a Zhoubaifu franchise store. Chanel failed to submit sufficient evidences to prove the unlawful uses of Chanel’s trade marks in the very store, such as soliciting customers or promoting products, that took advantage of the similarities between the products and Chanel’s trade mark registration. Therefore, the Guangzhou IP Court corrected the findings of the Haizhu Court on this point.

2. Confusion or misleading?

The Court found that there was no evidence of any circumstances to indicate that Ye misled consumers by advertising or marking the products in question as originating from Chanel. In addition, no evidence had proved that the ordinary consumers with a general level of understanding would deem that they were purchasing Chanel products in Ye’s store.

Additionally, Guangzhou IP Court opined that the aforementioned examination and determination on whether the shape of a product infringes exclusive trade mark rights should be conducted in a strict manner on a case-by-case basis. For the ‘commercial sign’ types of IPRs, such as trade mark and commodity packaging, the distinguishability and flexibility are integral to the scope of protection.

That is to say, in between (of these different commercial-sign rights) there should be sufficient distance, wherein the public can be freely to operate and create ideas. Considering the possible unlimited term of protection that a trade mark could provide, when deciding on infringements, it is of great importance to balance the interests of the public, as well as those of trade mark rights owners. The statutory measurements and standards should be strictly implemented to accurately determine the boundary of the exclusive trade mark rights, and to prevent the rights from improperly expanding at will. Otherwise, the normative stability of the market order will be adversely affected.

As a result, the Court ruled that Chanel had not made a sufficiently strong case, and thus rescinded the judgement of the 1st instance.

Comment

Some of the press comments pointed out that the final judgement ‘is no less than a justification for plagiarism by counterfeiting’, and it ‘in fact has denied the possibility of “transforming a 2-D trade mark of others into a 3-D product” as a type of trade mark infringement’. Sounds really bad, doesn’t it? Only, this Kat thinks otherwise.

The ruling did not ‘deny the possibility of (identifying) certain type of infringement’, there is quite a lot of space between ‘deny’ and ‘allow’… The core of the case is an issue of post-sale confusion (as it is hardly believable that the consumers who bought from Ye’s store would take the products as being made by Chanel). Notably, Chanel’s attorney also mentioned in his arguments that ‘trade mark confusion includes not only the direct confusion of origin, but also the other types, e.g. post-scale confusion, association confusion’. Why did this knowledgeable opinion not prevail? The answer is, plainly, that Chinese law has not adopted the post-sale doctrine. The status quo on this point, as reiterated by the Guangzhou IP Court, is that the confusion (stipulated in Article 57 of the Chinese Trade Mark Law) only refers to the ‘direct confusion’ caused by the misleading of producers or dealers.

The story of trade mark rights, in the context of modern society, has mostly been one of expansion. Yet a trade mark is not everything, it only governs a limited dimension of rights, and in this case, it happens to act unfavourably for Chanel. Nevertheless, under current Chinese IP law, Chanel still has several other options to make a case for the ‘Double C’ logo, for instance, copyright in works of art or unfair competition, for which, Chanel is free to submit claims in another case.

All in all, this Kat does not see the final ruling as an encouragement to counterfeit or infringe. Instead, it is a rightful decision that is in accordance with the current Chinese legislation. Although the trend might be, as has been submitted by many scholars, that the purpose of some IP regimes has been gradually made to preserve the status of luxury goods (see e.g. Professor Barton Beebe’s masterful article Intellectual Property and the Sumptuary Code), and it seems that many comments on this particular case have expressed such expectations of a pro-luxury goods decision, yet again, the Chinese trade mark law is just not there yet.

And last but not the least, having not adopted the post-sale confusion doctrine, from this Kat’s point of view, should not be seen as an indicator of less-advanced trade mark legislation.

Gif courtesy: Giphy

[Originally published on The IPKat on 4 January 2021]